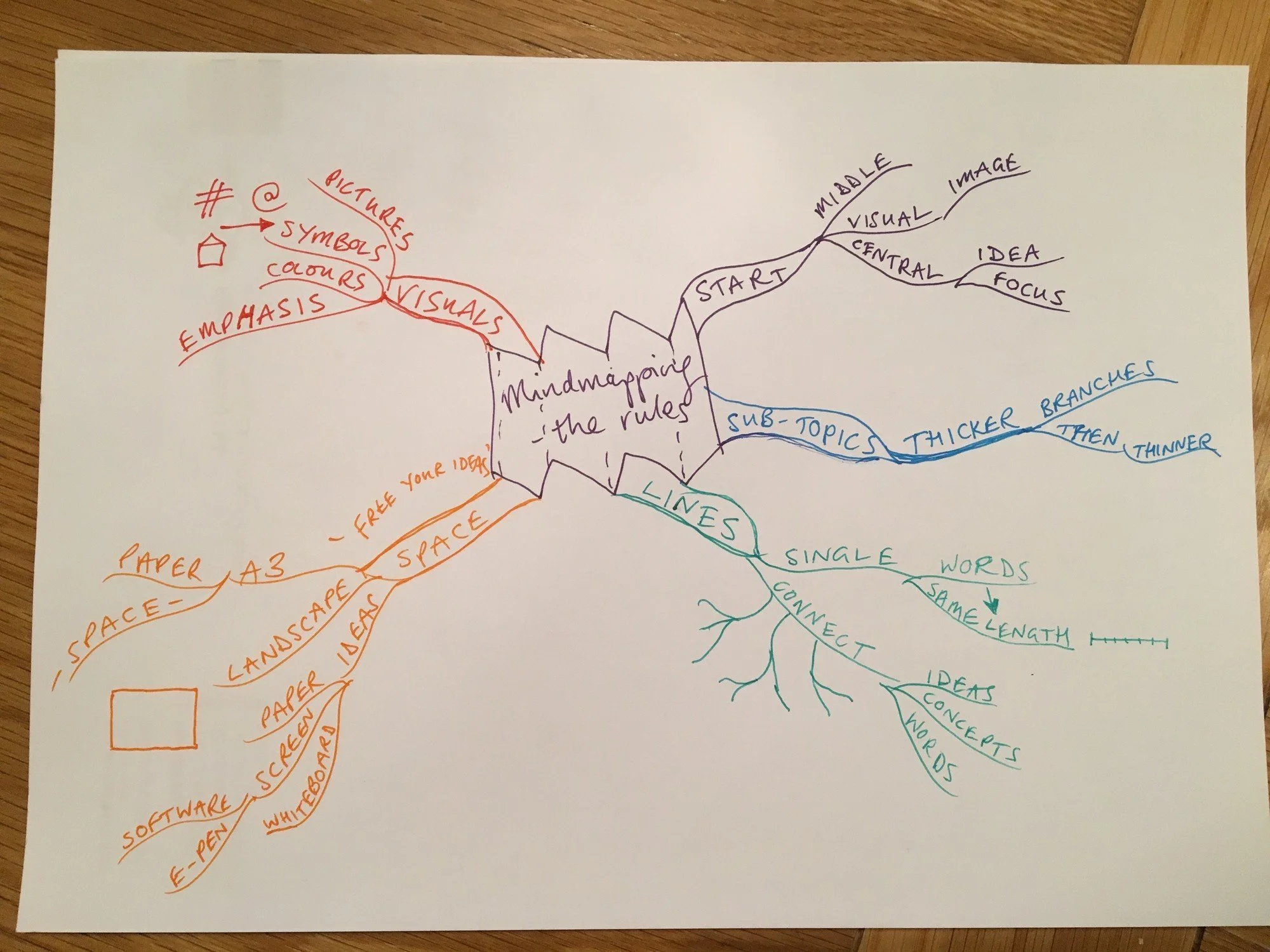

Making order from chaos: the 'rules' of mind mapping

For over twenty years, I’ve mapped my way through exams, a literature-heavy university degree and thousands of hours of data analysis in market research and education roles. Mind maps have been a crutch and companion to take notes, revise topics, organise, plan, braindump and brainstorm. They excel in helping to untangle complex concepts that refuse to be tamed with linear tables, lists and paragraphs.

These messy-looking word-webs are not for everyone, and can be easily misunderstood. I use them most often as a personal thinking tool, and not necessarily for wider communication. In recent years, however, I’ve shared maps to encourage discussion and in return had some queries asking about the process of mind mapping. Claiming no expertise here, it may be best to start with some of Tony Buzan’s classic rules, or at least the ones I remember most clearly:

Start in the middle, with your central idea/topic (preferably a visual);

Add sub-topics or concepts as the main, ‘thick’ branches around the central idea; as you move out from the centre, lines/branches become thinner;

Use only single words, on a single line as long as the word. Print words in upper or lower case (this forces you to underline and focus on key words and concepts, not getting lost in sentences);

Lines always connect to each other, so you're linking concepts and themes;

Ideally, draw maps on landscape, A3 paper so you have enough space to map ideas as far as they can go;

Use colours and visuals to help with focus, emphasis and communication of concepts.

A quick search for mind map rules will give you a more complete guide. Practically-speaking, when using mind maps as an everyday thinking tool without a suite of coloured pens and a stack of pristine A3 paper to hand, here’s what I come back to again and again:

Start in the middle, with your central idea or topic. If a visual comes to mind, by all means draw it – but the vast majority of my hastily-drawn maps just have those basic cloud shapes in the centre!

Write on lines, but don’t fret if you can’t capture the concept in a single word. It's really hard, though worth a try if you want to challenge yourself to really focus on the core ideas.

Use central branches as a way to focus thinking on the key concepts you’re analysing, planning or note-taking about. Add sub-topics to each of those as you discover more detail.

Think about it. The thinking process behind the hierarchies of words and concepts is really important. If the hierarchy gets stuffed up and things need to move to other areas on the map, that’s part of the learning and analysis process. Mind mapping software can help with this too - among other things, you can shift branches around really easily.

Use maps and iterate to explore how ideas and concepts connect. For me, this is a key advantage of maps over linear organising methods like lists, where I find it more difficult to work through how concepts relate to each other. Maps are more forgiving than writing line-by-line, and you can work with your own distractions to add to branches of the map as things come up, without losing sight of the key concepts and central topic.

So that’s it – some rules, if you need somewhere to start. Among the best advice in that original book was just to try it out, and map as much as you can. Use the rules to experiment, then bend and break them to find what works for your own style of thinking, analysis, note-taking and creative work.